Life as an Architectural Photographer with Kerataconus

Ironic as it is, I have what most people would describe as pretty bad eyesight.

Over the course of one semester at Uni, I noticed that I (fairly suddenly, to me, at least) I could no longer read the slides on the projector for any of my lectures. Sitting closer to the front didn’t help much either - the problem wasn’t that it was too blurry, but that the words were all overlapping each other.

I would later learn that I have a condition known as Keratoconus - in essence, a misshapen cornea, partly hereditary, and partly from having a lot of hay fever as a kid and rubbing my eyes a lot.

My eyesight deteriorated fairly rapidly during uni over the course of a year or so, and (thankfully) it’s now stopped deteriorating and I’ve become fairly accustomed to my new way of seeing.

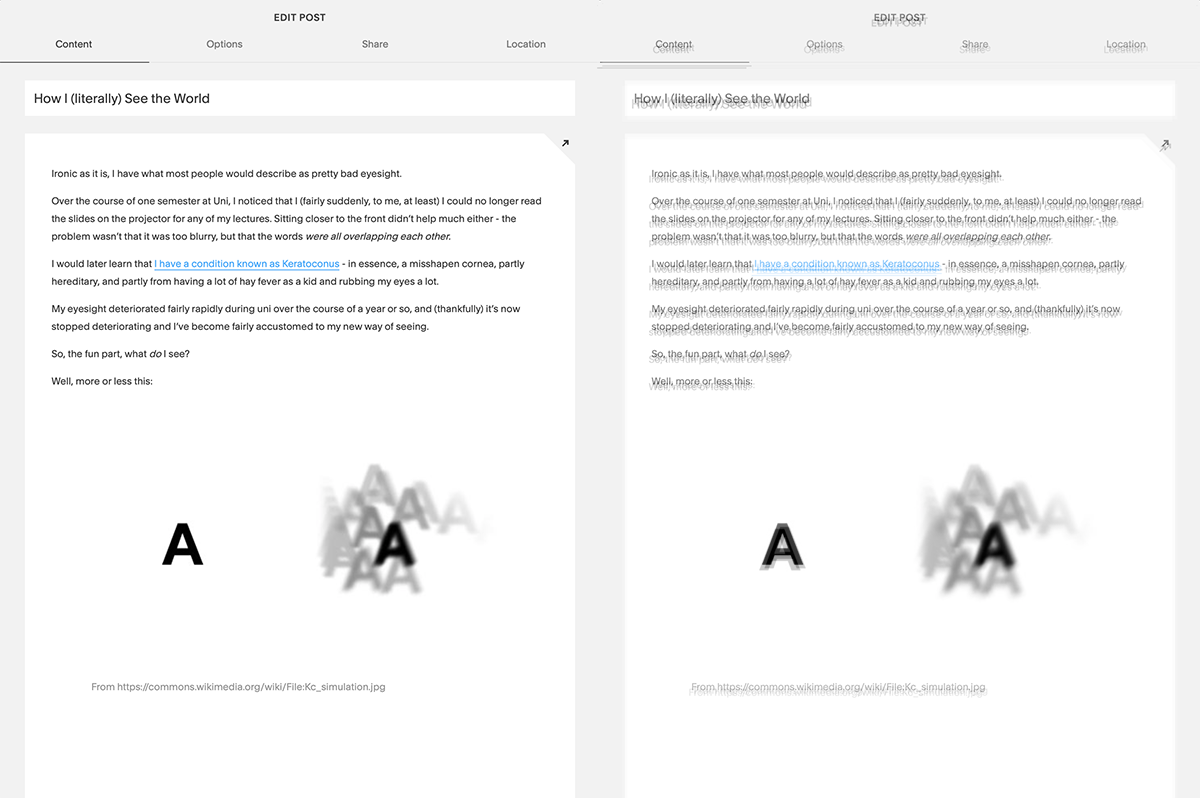

So, what do I see?

Well, more or less this:

From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kc_simulation.jpg

It’s called ghosting, and it’s interesting to say the least. Obviously, it makes reading anything on a screen fairly difficult, or anything to do with lights and high contrast at all for that matter.

For example, here’s a more accurate visualisation of the ghosting effect for me using this very blog post:

Left: This blog post. Right: How this blog post looks to me.

But it’s not just for reading and writing that ghosting can be a bit of a nuisance - I see like this all of the time. Whats great is that I’ve become accustomed to the effect - I’ve dealt with it for almost 10 years now, but it’s still always there.

I can’t recognise faces at a distance, especially in the dark, or read any signs after a certain distance - but not because they’re too blurry - there are just too many of them overlapping each other. It’s too hard to single out the ‘right’ object when I’m looking at something from far away.

The great irony of this is that I actually have really great eyesight, technically speaking; I just see too many of the same thing.

So the next great question - why do photography?

I find it much easier to ‘see’ my images through the blocks of colour and shape.

Luckily, the finished products are always nice and crisp compared to what I see.

Funnily enough, to me it just makes sense. Of course, I’ve always enjoyed photography in general, but I didn’t get into photography in a serious way until just after my eyesight deteriorated so much.

I think for me the reason that I do photography is also the same reason that I shoot architecture and interiors - it’s making things tidy. It’s making sense out of the shapes and textures that are all over the place, like pulling apart a puzzle.

Fortunately for me, a lot of the art of architectural photography is about lining up compositions and creating simple, yet effective, images that emphasise shapes, form and textures.

I’m incredibly lucky that I’m able to adapt a craft that I enjoy so much into what I do for a living on a daily basis, and (luckily) I seem to have gotten used to the eyesight condition in it’s current state.

Fingers crossed, it doesn’t change much further from here, but I like to think that, these days, it gives me a bit of an edge in my work.

Just don’t be offended if I don’t recognise you at a distance!